Hate crimes laws passed in Washington have been remarkably ineffective in protecting LGBTQ people for decades

Published in Political News

On Feb. 23, 2024, Daqua Lameek Ritter was found guilty of a hate crime for the murder of Dime Doe, a transgender woman from South Carolina believed to be in a relationship with Ritter.

The ruling marks both the first trial and first conviction of a hate crime on the basis of gender identity under the 2009 Matthew Shepard and James Byrd Jr. Hate Crimes Prevention Act.

Under the act, hate crimes are “violent acts motivated by actual or perceived race, color, religion, national origin, gender, sexual orientation, gender identity or disability of a victim.”

Between 2013, the year the FBI first began monitoring hate crimes motivated by gender identity, and 2022, the bureau recorded 1,969 hate crimes against trans and gender-nonconforming people, including a rise in 2022.

Ritter’s trial reflects low rates of prosecution for all hate crimes. Between 2005 and 2019, federal prosecutors investigated 1,878 suspects in hate crime matters, resulting in 310 prosecutions and 284 convictions for hate crime statutes violations.

I am a historian who studies the development of hate crime activism in Australia, Europe and the U.S. My research has found that hate crime legislation is strikingly ineffective at preventing violence through producing convictions, as is clear from the fact that it took 15 years to produce a conviction based on gender identity under federal law.

The legislation was hailed at the time by leading gay rights advocate Joe Solmonese as “our nation’s first major piece of civil rights legislation” for LGBTQ people. But it was not the result, as many believe, of unequivocally progressive impulses. Instead, it emerged from an unexpected convergence of gay and civil rights goals and a Reagan-era war on crime.

Through the 20th century, same-sex-desiring and gender-nonconforming people were often subject to violence and police harassment. Although early grassroots anti-violence initiatives in the 1970s offered some protection, LGBTQ people had little legal recourse.

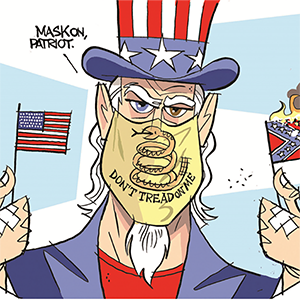

By 1980, 29 states still had anti-sodomy statutes on the books, and LGBTQ activists faced a backlash against limited gains of the 1970s. The 1980 election of Ronald Reagan, supported by an ascendant religious right, embedded this backlash in national politics. It also led to two important consequences for LGBTQ politics.

First, the medical reporting of what would become known as AIDS in 1981 among several gay men established a lasting association between homosexuality and deadly disease, triggering further resurgence of homophobia.

...continued

Comments